Associated Press

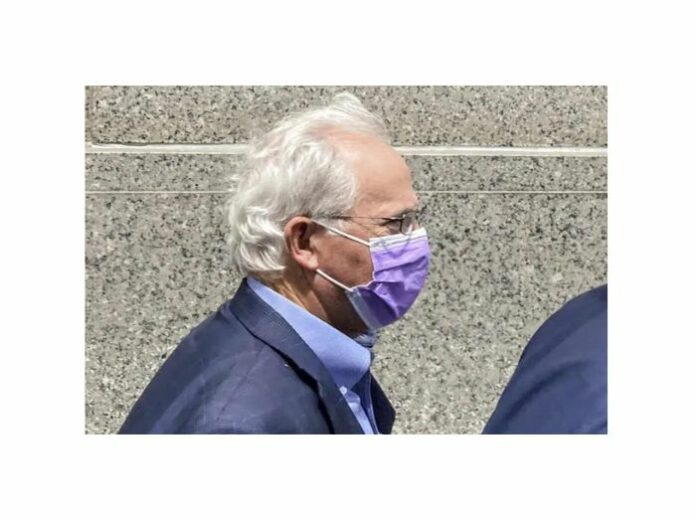

NEW YORK — Former U.S. Rep. Steve Buyer of Indiana went on trial Wednesday on insider trading charges, accused of illegally garnering stock windfalls by exploiting his consulting clients’ corporate secrets years after he left Congress.

During his 1993-2011 tenure in Congress, the Republican lawyer and Persian Gulf War veteran chaired the House Veterans’ Affairs committee for a time and served as one of the House prosecutors during former President Bill Clinton’s 1998 impeachment trial.

Buyer (whose last name is pronounced BOO’-yuhr) was indicted last year over stock trades made after he became a consultant and lobbyist.

Buyer represented Indiana’s Fifth District which included part of Kosciusko County.

“He took his clients’ information, inside information, and used it to line his own pockets, to give him an edge in the stock market the public would never have,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Margaret Graham told a New York federal jury in an opening statement.

Buyer’s lawyers counter that he was a stock market buff who did his research, made some profitable trades and didn’t even know about his clients’ private plans when he made the purchases that came under prosecutors’ scrutiny.

“Does lightning strike twice in the same place? Ask the Empire State Building,” Alonso said in his opening. (The skyscraper is hit by lightning scores of times every year, according to the National Weather Service.)

Buyer repeatedly bought Sprint stock in the weeks before the public announcement of the telecommunications giant’s planned merger with his client T-Mobile. The next year, Buyer made a flurry of purchases of stock in the management consulting company Navigant, which his client Guidehouse was set to acquire in a deal publicly disclosed weeks later.

Both buying sprees totaled tens of thousands of shares — more than he’d purchased in other investments — in stocks he’d never traded before, Graham said.

Buyer sold the stocks after the various announcements, making over $320,000 for himself, relatives and even a woman with whom he’d had an affair.

Prosecutors say Buyer made the buys after a T-Mobile executive told him about the Sprint deal on a Miami golf weekend, and after a Guidehouse sales director alerted him by phone to a company acquisition — without naming the company, but providing enough information for Buyer to figure it out. In both cases, prosecutors say the clients divulged the news in order to enlist Buyer’s help as a consultant, but he capitalized on it instead.

Buyer’s attorneys say the government is framing legal investment moves as a crime and won’t be able to prove that he learned of the impending corporate deals before making the stock purchases.

According to Alonso, the T-Mobile executive hasn’t said he’s certain he told Buyer about the Sprint deal in advance of the ex-lawmaker’s investment, and the Guidehouse sales director simply asked for Buyer’s help getting information on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs budget — a far cry from informing him that the company planned to acquire Navigant.

“He did research about both the stocks,” Alonso told jurors. “He actually had a good reason to want to buy them.”

Indeed, minutes before making his first Navigant purchase, Buyer emailed his son to note that stock analysts gave the company strong ratings. Prosecutors say Buyer was just trying to create a cover story for his newfound interest in the stock.

After financial regulators started sniffing around and Guidehouse lawyers interviewed him a couple of months later, he sent the sales director an encrypted message imploring, “I need to see you. Please,” and offered to catch the next flight, prosecutors said.

Buyer’s lawyer said the former lawmaker simply speculated that the acquisition target was Navigant, and that’s what he told the Guidehouse lawyers.

Buyer, 64, listened intently to the arguments, at one point asking one of his attorneys for a legal pad so he could write something down.

Buyer was an Army reservist with a solo law practice in Monticello, when he was called for active duty during the 1990-91 Gulf War. He served as a legal adviser in a prisoner-of-war camp.

While in Washington, Buyer helped draw attention to Gulf War-related illnesses, and he worked on other issues relating to the military, veterans, prescription drugs and tobacco.

Buyer later faced a complaint that he used his official position to get information on military absentee voters and help the Republican Party in the 2000 presidential election recount in Florida. The House Ethics Committee dismissed the complaint, filed by a Democratic member of Congress.

Buyer announced in 2010 that he wouldn’t seek re-election because his wife had a health problem.

The announcement came days after another ethics complaint, this time from a watchdog group concerned that a scholarship foundation he’d created had raised over $800,000 without yet giving any money to students.

Buyer said the charity was trying to build up a $1 million endowment before awarding scholarships. The Office of Congressional Ethics board closed its review of the complaint without taking action.