By Niki Kelly and Casey Smith

Indiana Capital Chronicle

FORT WAYNE — The man who prosecuted Joseph Corcoran for gunning down four men in 1997 probably wouldn’t do it again.

“Times have changed, my own thinking has changed,” Robert Gevers told the Indiana Capital Chronicle. “The death penalty is retribution. That’s all it is. Saving someone’s life is grace. So, are we a society about retribution or grace?”

Corcoran’s sister, Kelly Ernst, has a unique perspective — she’s his family, but also a victim. Corcoran killed her brother and fiancé.

“I don’t think his execution is going to help anything,” she told the Capital Chronicle. “It’s not going to provide closure for anyone involved.”

The impending execution is set for “before sunrise” on Wednesday and will be the first for the state of Indiana since 2009.

Gevers was the elected Allen County prosecutor for the 1999 case and handled the case personally. Since then, he has defended a death penalty case, coming to an agreement for that man to serve 300 years in prison instead.

Asked if he is comfortable with the state executing Corcoran, he said that’s not the right word.

“That was the decision back then. That was the job we did, and we chose it,” Gevers said. “And then ultimately that goes to the jury and judge, and they have the final say … if it were on my plate today, I would probably act differently.”

He mentioned that the sentence of life in prison without parole was new back then — but was likely a better option.

Corcoran’s mental health — not his guilt — has been at the heart of the case since the start. Gevers said he remembers psychologists testifying about mental health issues, but it didn’t rise to an excuse for his behavior.

“At that time, he was a pretty smart young man who was not using mental health to deflect or excuse or even explain. He wasn’t so mentally ill that it made me think, ‘Are we really doing the right thing?’ He was antisocial,” Gevers said.

He has had no interaction with Corcoran or his case in the last 20 years but has been reading articles and court briefs about his current mental state.

“Boy, I’m glad I’m not sitting on the bench,” Gevers said.

A long history of mental illness

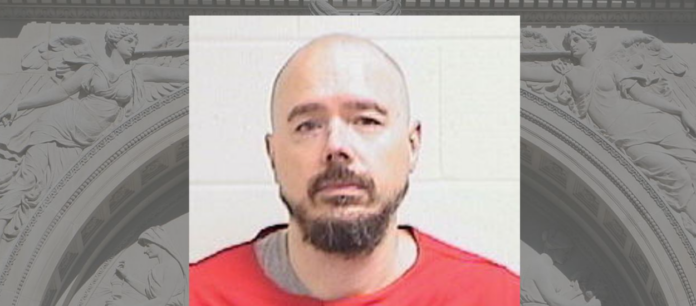

Corcoran – then 22 — killed his brother, James Corcoran, 30; Robert Scott Turner, 32; Douglas A. Stillwell, 30; and Timothy G. Bricker, 30, on July 26, 1997. He committed the murders at the home he shared with his brother and a sister.

Joseph Corcoran told police at the time that the four men had been talking about him. He first placed his 7-year-old niece in an upstairs bedroom to protect her from the gunfire before killing the four men.

He then laid down the rifle, went to a neighbor’s house, and asked them to call the police. A search of his room and attic, to which only he had access, uncovered over 30 firearms, several munitions, explosives, guerrilla tactic military issue books, and a copy of “The Turner Diaries.”

Earlier, in 1992, Jack and Kathryn Corcoran were found shot to death in their Ball Lake home. Joseph, their son, who was 16 at that time, was charged for their deaths. A jury later acquitted him of the murders, though.

Corcoran’s defense lawyers maintain that “severe mental illness” has caused their client to make decisions that aren’t in his best interest and have instead ensured his spot on death row.

Corcoran’s mental illness was documented in court filings as early as age 17, when he underwent a psychological evaluation following the deaths of his parents. Doctors who evaluated Corcoran over the last three decades have reached multiple diagnoses, including depression, paranoid schizophrenia and schizoid personality disorder.

State attorneys originally offered Corcoran a life sentence if he would accept a plea or waive jury. He refused, however, saying he would only agree to the terms if the state “would sever his vocal cords first because his involuntary speech allowed others to know his innermost thoughts,” according to court documents.

Later, at his sentencing, Corcoran stated that he wanted to waive all his appeals. And in the early 2000s, when the time was still ripe for Corcoran to initiate post-conviction review, he refused to sign the post-conviction petition.

So far, Corcoran has been unwilling to sign the necessary paperwork to initiate a clemency review or other avenues that could result in his removal from death row.

The inmate’s attorneys point to delusions that he has about ultrasound machines controlling him and his thoughts. But attorneys for the state say he is competent to be put to death.

They assert that Corcoran wants to be executed and has “a rational understanding of the reason for his execution.” The attorney general has additionally pointed to a 2006 letter and statements in years past in which Corcoran “admitted he fabricated this delusion.”

Last week, the Indiana Supreme Court sided with the state in a 3-2 decision, denying requests by Corcoran’s lawyers to delay his impending execution date and allow for his case to be reviewed or his sentence overturned. A different order issued by the court on Thursday again denied a stay.

Corcoran’s legal team is asking a federal judge to step in and pause the execution to allow for a hearing and review of their claims that putting the inmate to death is unconstitutional.

They argued that Corcoran’s mental illness has long distorted his reality and made him unable to understand the severity of his punishment. Larry Komp, Corcoran’s federal attorney, said his client “lacks any rational understanding of his impending execution — he simply wants to expedite the ending of the torture that is not real.”

That’s despite a November letter Corcoran sent to the high court, in which he said he has “no desire nor wish[es] to engage in further appeals or litigation whatsoever.” With his “own free will” and “without coercion or promise of anything,” he asked the justices to withdraw his counsel’s motions.

Ernst said she’s only resumed contact with her brother in recent months. Correspondence between the two was brief, at best, in the 25 years prior.

She was Corcoran’s legal guardian when the quadruple murder took place. She said it wasn’t until 10 years ago that she forgave Corcoran for the crime.

“I never expected what happened to happen in a million years,” Ernst said in a Thursday interview. “But what did happen pretty much changed my whole life. It was horrible. It sent me into a downward spiral. I was pretty self-destructive for a very long time. I had no contact with him after — just what I saw on the news.”

But execution, she said, “is not what I want to see.”

“And it’s bull*** to make it so close to Christmas,” Ernst said.

“He’s mentally ill,” she continued. “He’s been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, and when I was younger, I didn’t know what that was. I had no idea what mental illness was. But looking back, there were a few signs that I missed.”

Attempts to reach family members of other victims was unsuccessful.

Mark Thoma was one of Corcoran’s attorneys at his 1999 trial and he, too, is “appalled” that the state is going to put him to death when he “clearly” can’t make rational decisions.

“That’s just dandy. So, we’re going to let incompetent people make decisions?” Thoma said. “We’re now going to put to death a person who is seriously mentally ill. That’s what we are going to do as a society. How low can we go?”

But Thoma doubts Gov. Eric Holcomb will step in and stop the execution.

“I think it’s a stain on our government … And I can’t believe there aren’t more people up in arms about this,” he said.

Indiana governor weighs in

Holcomb — who has repeatedly maintained that he supports capital punishment when, “appropriate” — along with Indiana’s attorney general, announced in June that the state’s Department of Correction has obtained pentobarbital to carry out the death penalty.

Since then, the Republican governor has remained adamant that he won’t decide whether to intervene until it’s his “turn.”

When asked by the Capital Chronicle whether he considers Corcoran to be mentally ill, Holcomb said “he is,” but that “the courts have spoken to his ability to stand, to carry out the sentence and conviction.”

“I have read everything that (Corcoran) has written, what he said 20 years ago, what he says today,” the governor said, calling Corcoran’s November letter to the state supreme court “a hurdle to clear for his defense team — which he may be in disagreement with — which is interesting, to say the least.”

“I will reserve my final judgment until every step, every legal recourse and step, has been exhausted … when it becomes that the only option for change would be mine, not the court’s intervention,” Holcomb added.

Correspondence obtained by the Capital Chronicle detail requests by Corcoran’s lawyers to arrange a meeting with Holcomb. The legal team also offered to arrange a sit-down with Dr. Angeline Stanislaus, a forensic psychiatrist and chief medical director for the Missouri Department of Mental Health. Komp said the governor’s office has so far denied requests to meet, however.

Holcomb made clear on Thursday that he’s waiting for judicial proceedings to conclude before he takes any action.

“I’m still waiting for the court process to play out, and we’ll see what we learn. There’s still, I think, one more piece of the process that needs to occur,” he said, referring to Corcoran’s federal appeal. “This has gone before state and federal courts over the last 25 years, and they’re still, yet, part of that process to play out. And then we’ll make decisions based on the most current — and hopefully final information that we are in receipt of.”

Ernst, who has not been involved in Corcoran’s legal saga, said she had earlier hoped that Holcomb would stay the execution. Her message to the governor now, “is that his family wants a pardon. That’s what we want for him.”

“I respect her very much for her opinion. And that’s understandable,” Holcomb said in response. “I respect people on both sides of this issue, and I understand there are different degrees. I met with a lot of people on both sides of this issue. They know where I stand on the issue. I know where they stand. My job, as I see it, is to — as part of the process — to play my role. And the courts are what I look to — where he was sentenced and convicted, and time and time and time and time again, found to be competent to stand trial, and carried out the sentence. And that is the law of this land. And I took an oath to uphold the law of this land, and that’s what I will do, given all the facts in its finality.”

Thoma noted an online defense attorney chat board is full of outrage over Delphi killer Richard Allen’s case, but there is nothing about Corcoran.

“He’s not a very appealing defendant. He’s just not very likable. He has no personality. He’s a flatliner, shows no emotion. That’s the way God made him,” Thoma said.

He added that no one is disputing Corcoran is mentally ill and putting him to death is “barbaric.”

Pleas for a pardon

A delegation of faith leaders opposed to the death penalty descended upon the Indiana capitol Thursday to deliver a letter to Holcomb, imploring him to stop Corcoran’s execution.

The joint letter, with 70 signatures, emphasized that their call “to refrain from restarting executions in Indiana is an expression of our desire to honor the sacred dignity of all people, including both victims and those who have caused immeasurable harm.”

“Like many of Indiana’s civil leaders who share our values, we long to see the mercy, compassion, equity, and justice of God reflected in public policies that promote safety, human dignity, and healing for all Hoosiers,” the letter read.

A small group, led by coalition president David Frank, hand-delivered the letter to Holcomb’s office staff Thursday afternoon. A short prayer said aloud following the hand-off called for “changed hearts” and “changed minds.”

They prayed, too, for Holcomb to “have mercy” and peace during the Christmas season, and “to really reconsider” Corcoran’s death sentence. Holcomb was not present for the groups’ visit.

Their letter arrived at the Statehouse one week after Fort Wayne Republican Rep. Bob Morris called on Holcomb to block Corcoran’s execution — and death sentences for Indiana’s other death row inmates. The lawmaker additionally said he plans to introduce a bill in the 2025 legislative session to end capital punishment in Indiana, citing his belief that “only one position honors our Lord and Savior, our Creator: to protect all human life.”

Separately, a previous denial by the state’s correctional department to allow Corcoran to be accompanied by a spiritual advisor in the execution chamber was reversed on Thursday.

Komp, on Corcoran’s behalf, requested a “religious accommodation” for Corcoran’s execution in November.

Specifically, the death row inmate’s lawyer asked to have Corcoran’s Wesleyan minister “be present in the execution chamber with a Bible, be permitted to pray with Mr. Corcoran, and be permitted to have limited physical contact with Mr. Corcoran by placing a hand on his shoulder or holding his hand until the execution is complete.”

IDOC counsel originally refused, saying the agency “will not permit an outside person in the death chamber, as the safety, security and secrecy of those staff could be compromised.”

As of Thursday, an out-of-court agreement will permit Rev. David Leitzel to be present in the chamber with limited physical contact.

Ernst said neither she nor her twin sister will attend the execution.

“We just won’t,” she said. “We just think that’s another thing that’s going to stick with us the rest of our life.”